Swahili Isn’t Just for the Coast — Ask Eastern Congo

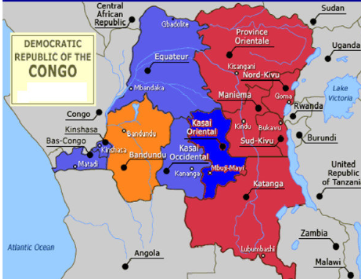

Geographical Context

Eastern Congo lies within the Tanganyika region, part of Africa’s Great Lakes. To its east are Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda; to the south, Tanzania, Zambia, and Malawi. Notably, the Nile River basin also flows through this area—an important detail, as rivers and lakes were once the highways of trade and cultural exchange.

The Swahili Coast and Its Roots

Between the 12th and 14th centuries, cities along the East African coast, from modern-day Kenya to Mozambique, flourished through trade. Goods like gold, spices, fabric, and ivory were exchanged with Arabs, Indians, and East Asians.

From this exchange, the Swahili language emerged as a lingua franca—a mix of Bantu, Arabic, and traces of other tongues. Scholars estimate that it is between 70% and 85% Bantu, with Arabic contributing around 12% to 20%.

Swahili Identity: A Complicated Label

In those early centuries, no one self-identified as Muswahili or Waswahili. In fact, some Arabs saw the emerging Swahili identity as impure—a diluted version of their culture. And many inland Africans saw Swahili middlemen as opportunistic or morally bankrupt.

Islam entered the region through a mix of Arab conquest and commerce, but it wasn’t only imposed. Over time, many indigenous communities converted, some by faith, others out of necessity. For those living along key trade routes, embracing Islam offered access to commerce, education, and upward mobility in the expanding Swahili world.

Eventually, Swahili-speaking Muslim communities established a strong presence in Tanzania, Kenya, and the Comoros. During Tanzania’s post-independence era, President Julius Nyerere declared Swahili the national language and proudly claimed a unified identity: “Sisi ni Waswahili.” This rebranding gave Swahili a political identity and instilled pride. Kenya’s coastal cities, such as Mombasa, reflected this with similar architecture, language, fashion, and food traditions.

You Can’t Speak About the Swahili Region Without Mentioning Eastern Congo And the Infamous Tippu Tib

Born Hamad bin Muhammad al-Muradi in Zanzibar, Tippu Tib was a Swahili-Arab trader from Zanzibar who rose to prominence in the 19th century. He became a central figure in the Arab slave trade that spanned East and Central Africa. His commercial empire extended into what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Tanzania, especially around Zanzibar and Lake Tanganyika.

He established a brutal network of trading posts to extract ivory and enslaved people from the interior. His expeditions raided villages, captured thousands, and funneled them to coastal markets. From there, many were sold and sent to the Arabian Peninsula, Indian Ocean islands, and occasionally even to the Americas.

Between 1884 and 1887, Tippu Tib laid claim to parts of Eastern Congo and aligned himself with colonial powers like King Leopold II. While some call him an explorer or merchant, his legacy is one of violent extraction and betrayal. He didn’t bring development—he built a pipeline of suffering, with Eastern Congo as a core hub.

Notoriously ruthless, Tippu Tib even sabotaged his fellow Swahili-Arab networks to gain European favor. But eventually, the colonial machine he supported sidelined him.

However violent, his presence in Eastern Congo proves how deeply rooted Swahili trade, language, and cultural networks were in the region, long before today’s borders were drawn.

Eastern Congo: The Forgotten Swahili Region

Despite its location in the Swahili-speaking Tanganyika region, Eastern Congo has largely been excluded from the broader Waswahili identity. Yet Swahili is spoken across cities like Goma, Bukavu, Uvira, and Fizi—not just in marketplaces, but in homes, schools, and churches.

No, we didn’t just pick up Swahili from a riverbank or a passing caravan; it was written into our region by blood, trade, and centuries of forced encounter.

The Swahili spoken here, sometimes called Swahili ya Congo, is more Bantu-leaning and less influenced by Arabic due to the fact that it is a majority Christian region that did not convert to Islam. Learning Arabic wasn’t mandatory for religious purposes—or as I would call it, religious colonization and cultural erasure. It reflects local cultural realities, not the Tanzanian standard.

Western Congolese, who mainly speak French or Lingala, often refer to Easterners as "Baswahili" or "Swahiliphones"—terms that reduce a linguistic identity to a stereotype, often with a dismissive tone.

Reclaiming Baswahili

Today, when a Congolese person introduces themselves as Muswahili, it’s more than just language—it’s identity. It’s a way to reclaim a name that was once given dismissively. In a country with over 250 ethnic groups and more than 200 languages, Easterners use Baswahili to signal their roots in Swahili-speaking culture, not just their proximity to it.

Personal Reflection

I was born in Congo, but we moved to Burundi for a short while as war overtook the East. We lived in Buyenzi, a district that felt like the Swahili coast. My father fished part-time and taught kids at school. Our neighbor, a Muslim woman, called me Feza, meaning “money.” Mornings smelled like vitumbua and mabajia, and my sister and I shared snacks bought with the change our father left behind.

We wore vitenge, including the kanga, which many associate with Swahili women—but for us, they were just part of our everyday life, purchased from the same markets that serve our neighbors across borders.

Eastern Congolese people aren’t outsiders to Swahili culture—we are part of its inland evolution. Our migration patterns, language, and customs are deeply rooted in it.

The Bembe tribe, for instance, is widely recognized across Tanzania. Many from Eastern Congo have successfully integrated into Swahili-speaking societies in Kenya and Tanzania.

A Call to Fellow Congolese

Let’s move beyond stereotypes. Learn the names of our tribes, cities, and languages—especially in Eastern Congo. Here’s a starting point:

Reference Page

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tippu-Tib